Jón Kalman Stefánsson

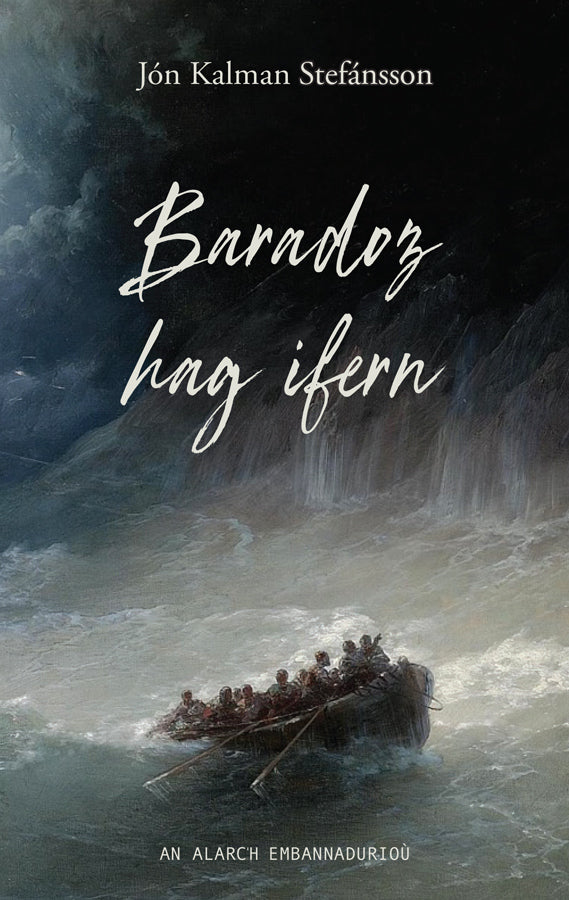

Baradoz hag Ifern (Himnaríki og helvíti / Between heaven and earth) by Jón Kalman Stefánsson

Baradoz hag Ifern (Himnaríki og helvíti / Between heaven and earth) by Jón Kalman Stefánsson

Couldn't load pickup availability

// Novel // History // published: 2007, translated into Breton in 2019 by Mich Beyer and Ólöf Pétursdóttir // 234 pages // An Alarc'h editions //

Published in 2007, Between Heaven and Earth is the first volume of a novel trilogy by Jón Kalman Stefánsson which was so successful in France that it gave rise to a radio serial .

A young sailor crosses the country, carrying a book that caused the loss of his best friend. From this minimalist plot, Jón Kalman paints a poetic and existential fresco.

Mich Beyer, a Breton-language teacher and writer, and Ólöf Pétursdóttir, a translator specializing in Celtic culture and modern and ancient Icelandic literature, have produced a Breton translation of the novel.

The Ísland gallery asked them about this work.

- This is the first time you've worked together; what brought you to this collaboration?

Mich Beyer : When I read the trilogy, I immediately thought it should be translated into Breton. So I contacted Ólöf, who was enthusiastic about the idea. We quickly realized that her Breton, although excellent spoken, was a little insufficient to convey Jon Kalman's very high literary level. So we decided to work together, with her translating and me reworking her text with the help of Éric Boury's brilliant translation. I also relied on the original text, sentence by sentence, for greater certainty, and I looked for a literal translation using dictionaries. Handcrafted work!

Ólöf Pétursdóttir : Indeed, Mich is a true Breton writer, and she quickly assimilates Icelandic. In reality, these two cultures and linguistic worlds are close, especially at the time of this novel. It is also true that my cursory Breton would not have had its place in the Breton text, but at least I am able to detect a slight misunderstanding or a discrepancy between the Breton translation of the French text and that sought for the translation of the Icelandic.

- Why did you choose this novel from the profusion of titles published in Iceland each year?

MB : It wasn't even a choice, just the encounter with this text that totally captivated me. I wanted to see it translated because I was sure it would "speak" deeply to British-speaking readers. Through the description of the living conditions of the time, the relationship with nature, the sea among other things, the human relationships, the poetic style... I also knew that there are quite a few absolute fans of Jon Kalman here. And I, who read quite a few Icelandic novels, put it at the top of the pile!

ÓP : Indeed, they are similar worlds and have a similar atmosphere. Jón Kalman could just as easily have been a young Breton author!

- How did you go about dividing up the work?

MB : Not really a pre-planned distribution, but back and forth, by email, between Ólöf's suggestions and mine, on the choice of this or that term, on punctuation, the use of tenses (a fairly complex and demanding area in Breton), the choice of certain figurative expressions specific to Breton, etc.

- More specifically, what are the grammatical particularities to take into account?

ÓP : The syntax is very free in Icelandic, as is the use of tenses. It was simply necessary to respect the meaning of the sentences, but not necessarily their form.

- To my knowledge, the use of the formal "vous" doesn't exist in Icelandic, but it does in Breton. Have you introduced it into the Breton text? If so, according to what principles?

ÓP : The formal use of the formal "vous" (you) existed in Iceland at that time [the time in which the novel is written] . Formally, it is actually the dual rather than the plural. It is not at all equivalent to the Breton "vous" (you).

MB : The latter is incredibly complex when spoken and depends on both the relationships between people (man/woman/child/social status, etc.) and the region/terroir. I opted for the informal form most of the time, as it's simpler.

- Does the structure of each of the two languages pose other translation difficulties (grammatical, lexical, etc.) from one to the other?

MB : Lexically, there are no real problems, except for one or two species of fish, living quarters... nothing insoluble, we adapt or add a footnote. In terms of sentence structure, it's more complex, and that's partly what I've worked on because we also always have to avoid the structure of French creeping in.

ÓP: Precisely, let's be wary of the structure of French. Icelandic is much more airy, much more manageable, with its tradition of short sentences aligned one after the other rather than affixed using prepositions, adverbs, etc. to create a sort of sea serpent that wouldn't do the trick in Breton either.

As for navigational vocabulary, the existing Breton vocabulary seems to borrow mainly from Old Norse/Icelandic. As for the form of oral tradition, it is more or less the same in Iceland and Brittany, and even across the entire Atlantic arc.

- Do you have any plans to translate the other books in the trilogy and/or other Icelandic novels or works?

MB : It's more than expected, we've started the translation of the second one (Harmur Englanna)! I didn't really think about it, but it turns out there was a demand...

ÓP: Indeed! To be continued. It should be noted that each volume of the trilogy is independent of the others. You can read one, two, or three, in any order.

- Beyond receiving this first translation, what makes you want to continue?

MB : I find this collaborative work fascinating, which is not very common among Brittophone translators, but which I consider necessary when dealing with less widely spoken or minority languages. It takes more time, it requires continual exchanges and questioning, but I believe that we gain a lot from it in terms of both fidelity to the original text and the naturalness of the translation. Readers must feel both transported elsewhere by the story and at home by the language of translation.

ÓP: Totally agree, the main thing is that the reader finds what they are looking for.

(1) which also includes The Sadness of Angels (2011) and The Heart of Man (2013), translated by Éric Boury and published by Gallimard.